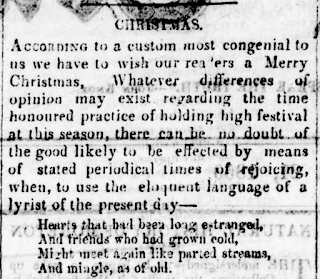

A Christmas message from The Moreton Bay Courier,

published on the 21st of December 1850.

*Preface* A century ago, it was customary to run Christmas ghost stories in the newspapers throughout the British Empire, a yearly event in which Australia also indulged - this tradition was most likely fuelled by the famous author Charles Dickens, who published many works on ghosts centred around the Christmas period. The newspapers of early Brisbane were no different - each year, a collection of ghost stories both fictional & real, would be published as a Christmas Supplement. So, in the spirit of resurrecting the age-old practice of sharing a local ghost story in time for Christmas, & without any further ado, please enjoy our "Ghosts of Brisbane's [Christmas] Past" article - & Merry Christmas to you all, from the Haunts of Brisbane!

To provide some historical context & validation for the following ghost tale of early Brisbane, we need to briefly examine the state of the region circa 1850. The event, which purports to detail an unexplained poltergeist outbreak, took place in a ramshackle premises in what we now know as Fortitude Valley. As a *fun fact* - & purely for the purposes of our yuletide tale - Fortitude Valley gained it's name after the resettling of immigrants brought to Australia aboard the ship Fortitude in 1849, as a part of the Rev. Dr. John Dunmore Lang's assisted immigration scheme, in a gully beyond the fledgling outpost of Brisbane. Quite coincidentally - the Captain of that ship, the first of three immigrant vessels to enter Moreton Bay, was John Christmas!

For those who follow the Haunts of Brisbane facebook page, we posted a teaser to this story a week back via an excerpt from The Moreton Bay Courier, advertising the issuance of Publicans licences on Monday 23rd December 1850 (pictured above). In amongst 3 separate licences that were issued on that date just prior to Christmas, one stands out - that of Jeremiah Scanlan's (spelt incorrectly in excerpt), for an establishment named The Strangers' Home - so we definitely know that an establishment, by that name, existed in Fortitude Valley as the region transitioned into 1851. From other period documents, we also know that the establishment existed on the corner of Queen Street (which would be renamed Ann Street in the early 1860's) and the New Farm or Race Course Road (also renamed later, to Brunswick Street) - for clarity, the original site rests below what is now a commercial building & The Beat Megaclub, diagonally opposite the now Royal George Hotel (or RG's as it's locally known, which at the time was the only other substantial structure in the region.

The licence renewal for the Strangers' Home Inn would eventually be refused in April 1854, providing us with a window of approximately 3 years within which the following poltergeist outbreak could have occurred (1851-1854). By 1854, the Strangers' Home Inn had already seen 15 months of upheaval. Around December 1852 (again, at Christmas), the Inn's original licensee, Jeremiah Scanlan, defected to a new premises of his own in the area, under the banner of St. Patrick's Tavern - the venue's owner, Charles Windmell, frantically attempted to transfer the licence but was refused, locking him in to continued trade at the Strangers' Home. By April 1853, at a time when our poltergeist was likely in action & the Strangers' Home's licence was yet again up for renewal, the Licencing Bench cautioned Charles Windmell & his management of the establishment that, "unless he reformed certain habits of intoxication that had been observed in public, his licence should not be granted for next year" - come 1854, it wasn't! Had the continued overt intoxication witnessed at the Strangers' Home Inn led to the belief in a "poltergeist" outbreak?? That, we will likely never know...however the following story stands as a fascinating report of early Brisbane paranormal activity!

[Taken directly from the Sunday Mail, printed on the 23rd March 1941]

SUCH a rational explanation of a poltergeist has never been found for an earlier outbreak in Brisbane, which, to some extent, resembled the famous Guyra Ghost. This ghost on the New England Tableland used to do its racketing and junketing at a house on the outskirts of Guyra.

Stones, some of them anything but small, fell on the roof of this house frequently at night, and the origin of them appeared to be mysterious in the extreme. The fame of this poltergeist travelled far beyond Guyra and the Tableland. It became, in fact, a major sensation of the Sydney and Brisbane press.

Additional police were sent to Guyra, and many persons, whose curiosity or superstition has been aroused by the reports, went also to inspect the house. Opinions differed widely as to whether the stone throwing and other weird outbreaks in Guyra were due to occult force, or had their source in some more that ordinarily expert larrikinism.

The Guyra Ghost ended with the suddenness with which it began, and if its manifestations were the work of that merry little cheer-up society, the poltergeists, then it was behaviour consistent with their record. The curious thing about any poltergeistical outbreak is, that a house haunted by them suddenly ceases to be haunted, and becomes once more fit for human habitation.

Apparently this was the case with the old Valley house in which, in the files, there occurred such a remarkable series of events and noises, for while the old files record the outbreaks, references ceased, and, so far as can be ascertained, did not appear again.

In the very early days of Brisbane an inn stood in Fortitude Valley, beside the timber-getter's track, which led out along what became Ann Street, to the big scrubs which then lined the banks of Breakfast Creek.

THE Valley itself was only sparsely settled, and the one shanty, which appears on the original licensing records as The Strangers' Home Inn, was sufficient for a time to serve the local people, the timber-getters, and general teamsters.

As the Valley showed signs of growing, the landlord of The Strangers' Home, decided to build extra accommodation. The additional quarters were erected at a short distance from the inn proper, and were of the type usual in those days. They consisted of a chain of rooms in a single-story building, facing on to an adze-hewn slab verandah, the whole structure roofed with bark.

About two years after it was erected, according to the accounts, began the first of a series of weird happenings, which have never had published explanation, if they had explanation sufficient to settle their nature to the satisfaction of the innkeeper, his guest, and frequenters.

One night, while teamsters and other early Valley workers were busy with the beer and rum in the long, low-ceilinged taproom, a man rushed into the bar and said that he had been struck heavily on the head by a rough wooden stool, which had suddenly bounded from the floor of his room in the new quarters!

DESPITE the fact that he was bleeding from a cut in the head, no one took much notice of him, for he was a recent arrival from the bush, who had been drinking heavily and steadily for days. They believed he had fallen and cut his head. He was induced to go back to bed. As the landlord, who had accompanied him, turned to leave the rough room there came a rending sound, and a joist fell from the roof, striking him so heavily that it broke his arm.

When a man in an adjoining room half an hour later was flung heavily from his bed a crisis developed. No one would remain in these quarters, and the taproom emptied its human contents to stand gazing awe-struck at the long building beneath a full moon on a mellow night.

No one would consent to sleep in the building for a full week, rolling themselves in their blankets on the floor and verandahs of the inn proper. Then, says the quaint old report of these happenings, "one citizen, equipped with more fortitude than his fellows, essayed the feat of laying the ghost."

He undertook for a bet to spend the night in the room in which the landlord himself had been struck. About 11 o'clock he settled down quite peaceably, but in a quarter of an hour there came a frightful noise of banging and rattling, and the courageous one came fleeing forth in his night shirt, with the bed gambolling after him, and shingles falling from the roof about him.

As there was not even a breeze the whole business was regarded as too perplexing for comprehension. That was the end of the annex to the inn. It was not afterwards occupied.

A reference to it about six months later in the Moreton Bay Courier says that the building was apparently free of the ghost-like visitations, but that nevertheless the landlord had decided to pull it down. Whether he did so is not known, but the advance of the Valley would, in an case, have disposed of it.

So for Queensland's poltergeists. Any one who is interested in the study of these strange antics in a wider sense may read Sacheverell Sitwell's "Poltergeists," recently published in London. English reviews state that Mr. Sitwell gives the detailed history of innumerable British poltergeists.

We are not likely to have many of them here. Possibly our climate is against them! Allowing exaggeration, or poltergeistical outbreaks are more likely to be "jokeristical" in their origin.

(Concluded)

*Postcript* The book referenced above - the 1940 edition of Sacheverell Sitwell's "Poltergeist," is available [HERE] for perusal & download for addition to your personal paranormal collections - amongst other reference materials, please download it before it's likely no longer readily available to access.